From the Not Just Numbers blog:

From the Not Just Numbers blog:

A time-taking Excel task that I see many clients accepting as necessary, is copying and pasting graph data every month to populate graphs that show a rolling twelve months. The data is copied and shifted back a month – pasting over the oldest month – with the new month’s data entered in the gap. As well as the time taken, this also has the drawback of losing historical data. The problem is only intensified if we are looking at weekly, or even daily, data.

Another approach I have seen is to enter the data continuously and edit the graph source data to look at the new range. This can still be very fiddly and even more hassle when there are multiple graphs.

If we apply my OAP approach to the problem, we come up with a different approach that requires little more than entering the new month’s data.

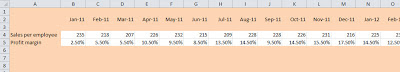

We first of all look at Obtaining the data. The simplest way to collect the data is to continuously enter the months as they occur – just entering each new month in a column out to the right.

We then look at Analysing the data – well, here we want to see whichever 12 months we wish to report on in the same place every time, so that we do not need to move data, or redirect the graphs.

Finally, we Present the data by pointing the chart at the 12 month sheet.

We just need a simple system to populate the graph data sheet with the 12 months.

The OFFSET function is a great tool for this.

Enter the month at the top of each column in the main data sheet, going out to the right as far as you want into the foreseeable future and enter the data each month as it happens, e.g.

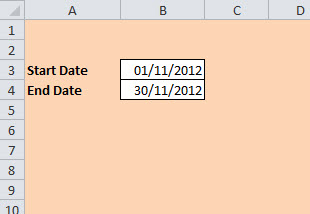

On a second tab you want a similar layout but with only 12 months. The only data you enter on this tab will be the current month (in cell M2). I have used the date format mmm-yy throughout with all dates being the first of the month.

The month in cell L2 is calculated using the formula

=DATE(YEAR(M2),MONTH(M2)-1,1)

this can then be copied back along the row as far as B2, each time it calculates the 1st of the month before. The DATE function is covered in this earlier post.

Then cell B1 includes the function:

=MATCH(B2,’Data Entry’!$2:$2,0)-1

This looks for the date that is in B2, in row 2 of the Data Entry sheet and returns how many columns along it finds it. I have deducted 1 from the result to provide the number of columns to offset from column A to find the correct data.

Cell C1 is just B1+1, continuing in the same vein along the row to M1 (=L1+1).

We then use the OFFSET function in the data fields to use the number in row 1 to pull in the correct data from the data entry sheet.

The formula in the first item of data in cell B4 is:

=OFFSET(‘Data Entry’!$A4,0,’Graph Data’!B$1)

This returns the cell that is offset from cell A4 of the data entry sheet by zero rows and B1 (11 in the example) columns.

Notice the dollar signs. By applying the dollar signs as we have, when copied along the row, the formula will continue to look at column A of the data sheet, and when copied down, it will continue to look at row 1 of the Graph Data sheet. Meaning that the formula can be copied all the way across and down to as many data fields as we want to add.

Set up all of your graphs to point at the 12 months on the Graph Data sheet and you will never need to change them.

In future, you just need to enter the data in the data sheet as it becomes available, and enter the last month of the 12 month period you want your graphs to look at in cell M2 of the Graph Data sheet.

I hope you’ve found this useful. I am currently planning some video training packages and I would really appreciate it if you could use the comments below this blog post (and others in future), to let me know what you find most useful about these posts – and what you don’t – to help direct my planning.

If you enjoyed this post, go to the top of the blog, where you can subscribe for regular updates and get your free report “The 5 Excel features that you NEED to know”.

.jpg) If you have subscribed, you’ll be hearing from me on Christmas Day, with your exclusive Secret Santa Gift.

If you have subscribed, you’ll be hearing from me on Christmas Day, with your exclusive Secret Santa Gift.